Summary

- Tesla has laid off over 14,000 employees, but the hardest hit was the supercharging network development and deployment team, which had every employee out the door last week

- Tesla’s big push into the DC Fast Charging (DCFC, or Supercharging) network was one of the biggest initiatives that helped EV sales skyrocket over the last decade

- Tesla owns roughly 62% of all of the charging infrastructure across the USA

- Of the other 38%, multiple companies now have a huge opportunity to expand and build up in big EV markets, including Texas and New York City

- We think that Tesla decimating its own charging department opens the door for another company, maybe even an automaker like the VW Group, to take up the mantle of DCFC station deployment and development

A couple of weeks ago, we reported that Tesla was going to cut its workforce by 10%, affecting over 14,000 employees. Now that we’re into May 2024, it has come to light that one of the departments hardest hit by the layoffs was their charging network development and deployment team.

The layoffs have effectively decimated the entire department, according to AP News, with the department of about 500 employees all being laid off. While the department still exists in name only, no one is actually working there anymore. This raises one very important questions that begs investigation and analysis:

Who actually owns what part of the charging network across the USA?

Tesla Is/Was The Big Investor

As of January 2024, there were approximately 31,000 DC fast charge stations deployed across the United States. Of those, Tesla owned a staggering 19,250, or roughly 62.1%. It should be noted that to be considered a DC Fast Charging (DCFC) station, it must be Level 3 and provide at minimum a continuous 50 kW of electricity to the vehicle, but more commonly range between 100 to 200 kW.

Because of this huge investment into charging, many automakers that have diversified into making EVs bought into the Tesla charging network, either through making their vehicles use the same type of connector as Tesla cars, or by having an adapter to make their vehicles compatible with multiple charging standards.

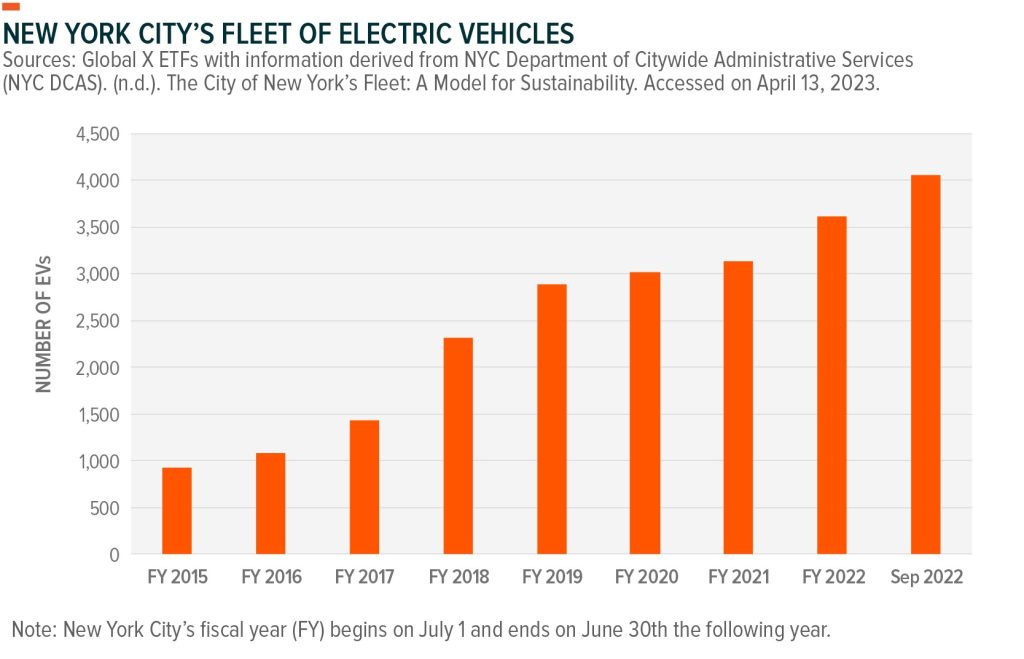

The layoffs have immediately ceased new Supercharger deployments in Texas and New York, despite having buying up the land and running the power infrastructure to support multiple superchargers. These would have further expanded Tesla’s presence in two of the states that, next to California, buy the largest amount of EVs.

The combined impact here is that without a charging department at Tesla anymore apart from in name, there are no new adapters or plug styles being developed, but more importantly, the first-party support team is gone. Once seen as the gold standard in the industry for speed of repairs, if a Supercharger breaks or has an issue now, it will be handled by a contracted third party from ticket to resolution.

Looking at it analytically, with over 60% of the US using Tesla’s network, this poses an incredibly significant risk that that network’s reliability could degrade. As well, with no one working with automakers now to ensure compatibility with their vehicles, this could cause no end of headaches in the next few years if those vehicles don’t “talk” to the supercharger network.

The Other 40%

Well, 37.9%, but we’re rounding up. Of note, almost all these stations use the much more common J1772 & CCS plug type, and if your EV has CCS1 compatibility, you can charge at up to 350 kW depending on how busy the charging station is.

With approximately 11,750 DCFC stations remaining, fully a quarter of them, 26.1% or 3,062, are owned and operated by Electrify America (E.A.). They are by far the largest non-Tesla operator, and even have a subsidiary company that services Canada with the highly original name Electrify Canada, and is the biggest non-Tesla network there too.

21.4% (2,519) of the remaining stations are operated by EVGo, the other really “Big” charge network apart from E.A. Both E.A. and EVGo use a monthly subscription model to subsidize maintaining their networks and expanding, although both also offer a “pay as you use” plan that adds a small surcharge to each “fill-up” to offset the cost of their network being used.

ChargePoint is the next biggest operator, with 16.9% (1,980) of the the non-Tesla network, and are the last big EV charging specific company.

Surprisingly, non-networked DCFC stations make up the next biggest percentage at 9.1% (1,071). These are charge stations either owned by a company that does not need you to subscribe or have an account to access, are the kind you find in hotel parking lots included with your room fee, and/or are located at the corner convenience store such as 7-11.

Shell’s foray into EV charging, Shell Recharge, is the next biggest at 4.7% (551), although 90% of those stations are in California as that is where the pilot program is being tested. The Free Charging Network, a non-affiliated group that is hoping to accelerate EV adoption through no-surcharge charging points, makes up 4.6% (546) of the non-Tesla stations.

The remaining 17.2% is split up among EV Connect with 3.7% (430), EVCS with 2.3% (269), Rivian Adventure at 1.54% (181), and all other independent charge stations (mom-n-pop service station, free-standing independently owned station, et al) at 5.1% (599).

What This Means Looking Forward

There is no argument that Tesla is/was the biggest driving force for adoption of EVs across America. While their network has no plants to shut down, by effectively shuttering the charging department at Tesla HQ, it opens the door for other companies such as E.A. and EVGo to swoop in and build up their market presence.

In the grand analysis of Tesla’s overall business model, there is a strange kind of logic to slicing away the charging department. EV adoption has levelled off almost entirely across the board, and the key thing Tesla needs to do is get their vehicles to customers at lower prices.

It happens all the time in other businesses, especially the gaming industry, in that once a project is finished, a whole team of people can be let go to save money and redirect it to support and production elsewhere.

If the money that would have been going to the charging team gets redirected to slashing production costs, which in turn lowers the sticker price of a new Tesla car, that might be just enough to get new and returning customers to pull the trigger on one of their vehicles instead of a competitors.

We think that the next couple of years are going to be very interesting. Who will pick up the slack in deployments and developing new connector types? Does this open the door for VW Group, who are betting hard on EV adoption by 2030, to pick up the mantle as the lead developer of new charging tech/stations? If Tesla recoups their losses, will they rebuilt their supercharging department?

Meaning it seriously, only time will tell…