For readers with an interest in China’s New Energy Vehicle market, when the manufacturer SAIC gets mentioned, the company’s Roewe brand is probably the first brand that comes to mind.

There is good reason for this. Last year, during 2018, of the four SAIC models that made the list of China’s Top Twenty NEV sellers, three of the four carried the Roewe badge.

The exception was the Baojun E100, a micro two-seater made by SAIC’s joint venture (JV) with GM and Wuling. SAIC is the majority share holder, owning just over 50 percent of the company.

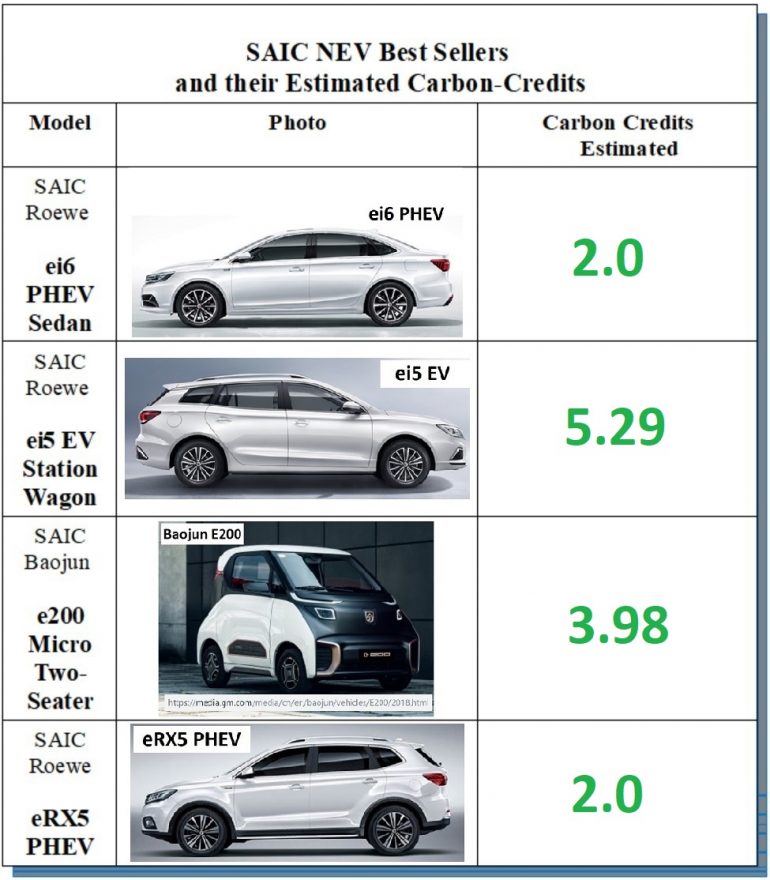

The four best selling “SAIC” models are listed and pictured below:

-

- the Roewe eRX5 PHEV SUV,

- the Roewe ei5 EV station wagon,

- the Baojun E100 two door micro (a product of the SAIC-GM-Wuling Joint Venture), and

- SAIC Roewe ei6 PHEV sedan.

The Baojun E100 gets an Upgrade (Baojun E200 aka the New Baojun E100).

During the second half of 2018, the SAIC-GM-Wuling JV began selling an upgraded version of the Baojun e100, which is described in a General Motors June 2018 press release here as the New Baojun E100. As noted in the release the primary aspect of the upgrade is the longer driving distance, 200 km, which is about 30% more than the previous 155 km. range.

According to another GM China news reference here, a “new” model, was launched in September of 2018. Referred to as the Baojun E200, the “new” model appears to be the same model as the New Baojun E100 that was earlier highlighted in the June 2018 press release, despite the fact that the Baojun E200 reportedly has a slightly higher driving range of 210 km. (NEDC). The lack of consistent terminology regarding model names certainly can be confusing, even for this patient blogger. What is now clear, after cross-checking multiples sources, and the details of specs, is that Baojun’s micro two-seater vehicle, that has a reported driving range of 210 km (NEDC) – – whether its called the E200 – – or the New E100; is indeed the same model. Because the model is still referred to by most sources as simply the E100, I’ve conformed to that label (E100), for almost all sections of this blog. The exception is the section or content related to carbon-credits, where I’ve sometimes used E200, because the Baojun E200 has a longer range (210 km) which matters significantly when calculating carbon credits. To make matters even more challenging, Zotye has its own e200 model, which is not to be confused with the Baojun e200. Good. Clear as mud 😉

So which model is the hottest?

Although all SAIC’s four models pictured above sold relatively well last year, only one – – the Baojun E100 – – experienced a surge in sales during the last quarter of 2018. During the last three months of 2018, nearly twice as many E100s sold as compared to SAIC’s other best sellers.

In the micro two-seater car segment, only one other model – – the Zotye e200 – – made the list of Top 20 Best Sellers in the NEV category. Both micros are similar in size and shape, as seen in side by side photo below:

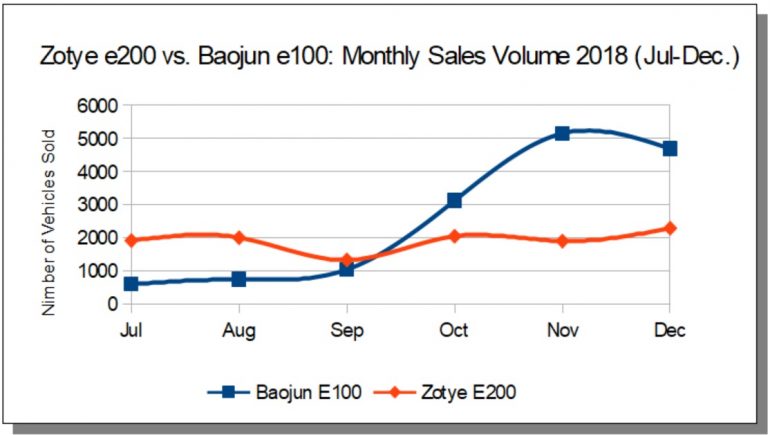

Although the Zotye E200 outsold Baojun’s E100 during the third quarter of last year, in the fourth quarter, Baojun’s two seater began to clearly overtake its Zotye competitor by a wide margin as seen in the graph below:

While we don’t know exactly what contributed to the Baojun E100’s dominance during the fourth quarter of 2018, a number of factors or developments are worthy of consideration:

-

- Prior to mid-2018, the geographic market for the Baojun E100 was limited to Guanxi province, a southern province bordering Vietnam. However, in June-July of last year, Baojun began expanding the E100’s market by selling the two-seater in the Northern province of Shandong, in the area of Qingdao.

- The map on the left below shows a zoomed out view of Guangxi and Shandong (see red rectangles), as well as the location of Shandong’s Qingdao city. The map on the right shows a zoomed in view of Qingdao – – which as a matter of interest – – includes a nearby Zotye “New Energy Dealership.”

-

- In all likelihood, numerous factors led to Baojun’s decision to sell its E100 in the Qingdao region. It seems plausible that the opportunity to compete directly with Zotye’s E200 was at least one such reason.

Baojun’s entry into the Qingdao market during the second half of 2018, most likely contributed to the E100’s success during the Oct.-Dec. period (see graph above), when Baojun’s E100 decisively began to outsell Zotye’s E200.

Although the graph pertains to national level sales, we know that prior to the third quarter of 2018 the E100’s market geography was limited to Guanxi province in south China. Given that Baojun’s E100 entry into the Qingdao market did not begin until June-July, and considering that it normally takes a few months before sales volume for a successful product begins to ramp up in a new market- – it seems reasonable to suggest that the Baojun E100’s expansion into Qingdao likely contributed to the large rise in sales volume during the fourth quarter of 2018.

Baojun as a brand is known historically for its success outside of China’s largest cities; in other words in China’s more rural areas or in smaller towns and cities. Qingdao is one example of a second tier city. These market geographies, because of their lower rates of car ownership, and their associated higher rates of sales growth, are attractive to not just Baojun or Zotye looking to expand their business, but to virtually all the major OEMs, whether domestic (like SAIC and Geely) or international OEMs such as GM, Ford, or VW. As a case in point, Ford, together with its joint venture partner JMC (Jiangling Motor Co.), is expected to launch a new SUV (the Territory), into the Qingdao market during early 2019, as noted in the article here.

GM already has an established presence or foothold in China’s market for micro EVs, because of the earlier mentioned SAIC-GM-Wuling joint venture; which owns and produces the Baojun brand.

Small NEVs in China and rapid growth. Why?

China’s New Energy Vehicle/NEV market grew by 62 percent year-on-year (2018 vs. 2017), with 1.25 million NEVs sold during 2018. As noted in a China Daily article here, 2019 sales are expected to reach 1.6 million. Within the NEV segment, small vehicles, meaning micros and compacts, are selling best. China’s government refers to these small vehicles as “A00” or “A0” type cars. Within this context “micro” is synonymous with A00, while the slightly bigger, but yet still small “compact”, is roughly synonymous with A0.

In general, its hard for OEM’s to make money selling small, inexpensive vehicles, with very thin profit margins. Its even harder with electric vehicles, which is why governments subsidize them. When the occasional or rare scandal occurs (i.e. a subsidy recipient/OEM committing fraud to improperly receive subsidies) as happened in a few limited cases in China in recent years, this can further delay government subsidy payouts to all OEMs – – including the vast majority which are innocent of any wrong doing. When government subsidies are late, or unreliable, OEMs feel the squeeze, in terms of their corporate balance sheets, cash flow, or profits.

So how is it possible, that despite all of the challenges mentioned above, China’s market for NEVs – – and especially small pure EVs (vehicles powered by batteries only) – – has been experiencing rapid growth during recent years and months?

Much of the growth is a result of the both “carrot and stick” approach that China’s government is using to promote the transformation of China’s automotive market and industry, away from its current and historical reliance on traditional/conventional cars (Internal Combustion Engines/ICEs) and towards much greater reliance on EVs and hybrids (New Energy Vehicles). But that transformation is expensive, and China’s government would like to shift that expense away from public coffers, and towards the OEMs.

This year 2019, marks an expected transition, meaning that later this year China’s long anticipated carbon-credit trading system for the automotive sector is due to begin. This will have major implications not only for companies like SAIC, GM, Baojun, Zotye etc. – – but for all manufacturers in terms of their production, and more specifically, the mix of their output regarding ICEs and NEVs produced. In short, manufacturers will have three choices:

a) produce more NEVs to meet quotas, that are specific to each manufacturer, as determined by the new regulations,

b) don’t meet the quotas but comply with the policy by purchasing carbon-credits from other NEV producers (i.e. competitors) whom have earned surplus carbon credits,

c) face stiff and costly fines and penalties for doing neither a) nor b) above.

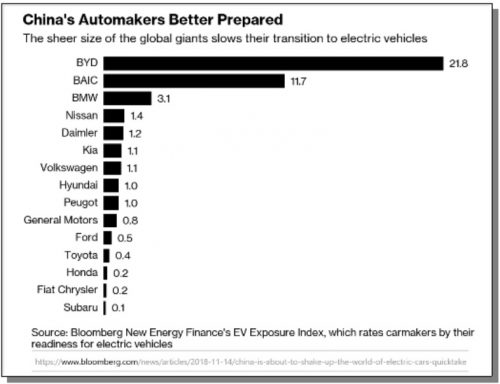

Bloomberg’s New Energy Finance team has created an innovative EV Exposure Index to reflect the “readiness” of OEMs for EVs. As seen below, the Chinese OEMs BYD and BAIC score high or “most ready”, because of their high production rates of NEVs. On the other end of the spectrum, manufacturers with low ratings include Toyota, Fiat-Chrysler, Honda, and Subaru. As seen in the graphic below, GM and Ford have readiness index scores that are a bit higher, however still low, relative to NEV industry leaders.

GM’s partnership with SAIC and Wuling, via their JV, is interesting to examine, from the perspective of – – “What’s in it for GM?” In a very insightful 2017 commentary article here (Thriving Baojun bodes well for GM’s future in China) the Managing Editor of China Automotive News, Yang Jian, addresses this question, and highlights some important strategic considerations. Some excerpts from Jian’s 2017 commentary appear below:

-

Baojun is successful because it has never lost its focus on entry-level car buyers. The brand targets customers in rural areas and small cities in China where the main competition is domestic Chinese brands.

-

it (Baojun) has been given a new goal: Help GM expand into China’s EV market to meet Beijing’s production quotas. In 2019, the government will introduce a California-style carbon credit trading program to goad automakers to ramp up output of EVs and help curb emissions and pollution.

-

In response, Volkswagen and Ford each have formed new joint ventures with Chinese EV makers to build small, affordable EVs. GM doesn’t have to do this, because Baojun has access to an entry-level market that Ford and VW have never tapped.

-

To be sure, Baojun doesn’t boast the profit margins of Buick or Cadillac (two other important GM brands in China). Starting prices are below 70,000 yuan ($10,600), but manufacturing costs are modest, too, so Baojun is a money maker.

Readers should keep in mind that the excerpts above are from a December 2017 article, when Baojun’s business was thriving. As noted in a much more recent February 2019 article here, business for GM’s two joint ventures in China, SAIC-GM, and SAIC-GM-Wuling have taken a downturn, with sales declining significantly during 2018.

Back in November of 2017, GM’s China Chief, Matt Tsien, quoted in a Reuters article here, expressed his confidence, in GM’s ability, and the abilities of its JV partners to meet China’s NEV quotas, which begin this year. The accompanying photo to the Reuters article showing Baojun’s E100 assembly line, represents a good example of the old saying “a picture is worth a thousand words.”

So given much of what’s been presented above, I thought it would be interesting to start taking a look at OEM’s and their ability to generate carbon credits, using the Baojun E100 as an example. Although we won’t be able to get a solid understanding of the more important question – – (i.e. “How much financial value are the carbon-credits going to be worth?”) – – it still seems timely, given the expectation that China’s carbon-credit trading system will be launched sometime this year, to begin looking more closely at OEMs, and their ability to generate carbon-credits.

So given much of what’s been presented above, I thought it would be interesting to start taking a look at OEM’s and their ability to generate carbon credits, using the Baojun E100 as an example. Although we won’t be able to get a solid understanding of the more important question – – (i.e. “How much financial value are the carbon-credits going to be worth?”) – – it still seems timely, given the expectation that China’s carbon-credit trading system will be launched sometime this year, to begin looking more closely at OEMs, and their ability to generate carbon-credits.

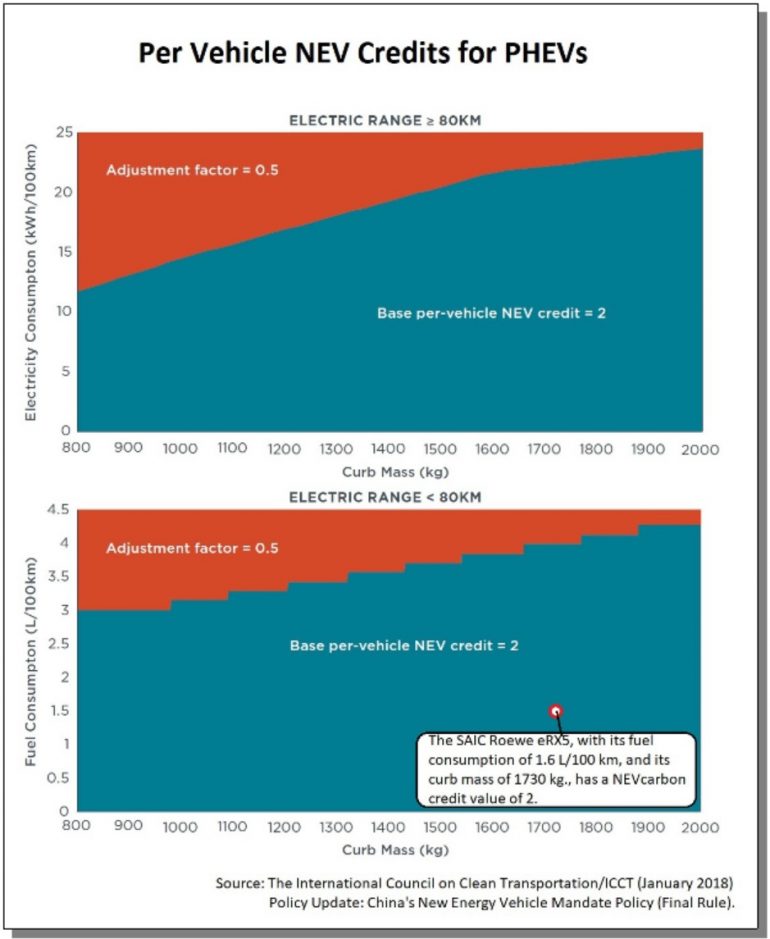

For readers that are interested in the details of how carbon-credits are calculated, the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) has produced an excellent Policy Update (January 2018) titled China’s New Energy Vehicle Mandate Policy (Final Rule), which is the source I used for estimating carbon credits within this blog.

How Many Carbon-credits are earned for producing one little Baojun micro two-seater?

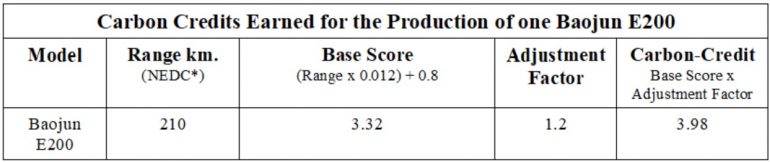

Below is a table that approximates the carbon-credits that the SAIC-GM-Wuling joint venture will earn, for the production of a Baojun E200 vehicle. As a reminder, readers might wish to revisit the earlier section above (see “The Baojun E100 gets an Upgrade” for an explanation of Baojun model numbers, E100 vs. E200 etc.).

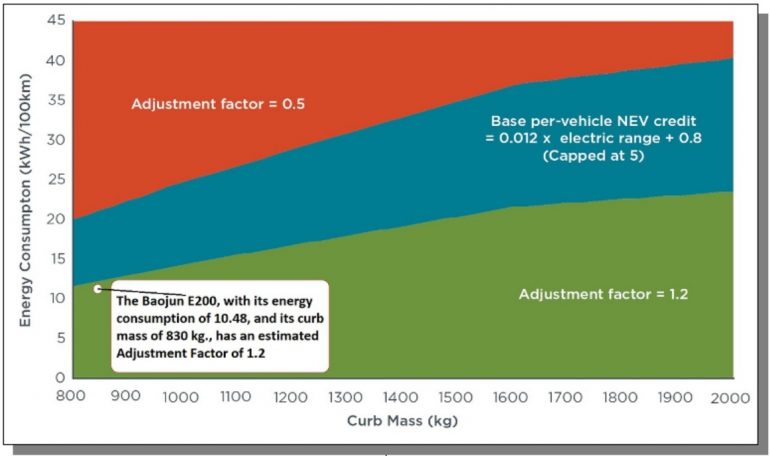

Carbon credits for pure EVs are capped at six credits; irrespective of Base Score and Adjustment factor. Six credits is the maximum number of credits that any pure EV can earn. The ICCT Policy Update includes helpful graphics that illustrate how the adjustment factor is determined, depending on a given vehicle model, and its specs., in terms of energy consumption, and the mass or weight of the vehicle. I’ve annotated the original ICCT graphic below, by inserting the Baojun E200 into the picture:

In addition to the micro two-seater E200, SAIC will be earning carbon-credits from its other NEV models. I thought it would be interesting to look at how many carbon credits the various SAIC NEV models (i.e. 2018 best sellers) would generate, on a per unit basis, which is shown in the table below.

It is important to note that there is a separate and distinct method for calculating carbon credits for PHEVs – – and that method is different than the method used for pure EVs.

For PHEVs the associated carbon-credit is either two or one, depending on whether an adjustment factor is applied. As seen in the graphic below, PHEVs with certain specs. are adjusted

downwards/lower with regards to their carbon credit value, by applying a multiplier of 0.5 to their base value of 2. For such cases, the result is a carbon credit score of 1.

This method applies both for:

- PHEVs that have an electric range of 80 km. or higher, and

- PHEVs with an electric range of less than 80 km.

For PHEVs with electric ranges above 80 km. – – energy consumption (kwH/100 km.) is used together with curb mass (kg.) to determine the adjustment factor. Alternatively, for PHEVs with electric ranges below 80 km., fuel consumption, as measured by L/100 km., is used. These methodology specifics are more clearly illustrated in the graphic below. The SAIC Roewe eRX5 is used as an example in the bottom most graph. The eRX5 SUV has a carbon credit score of 2, due to its electric range of < 80 km., its fuel consumption rating of 1.6 L/100 km, and its curb mass of 1730 kg.

The table below shows all four of SAIC’s 2018 best selling NEVs, and their estimated carbon credits, using the appropriate method either for pure EVs, or for PHEVs:

It’s clear from the table above that SAIC’s pure EV models generate more carbon-credits, on a per unit basis, compared to PHEVs. This reflects Chinese government policy, which favors pure EVs. If we look at the first two models in the table above, we see that selling one ei5 EV wagon, generates over five credits, more than twice the credits generated from selling one ei6 PHEV sedan.

The value of the credits won’t be known for some time, given that the NEV carbon trading system is yet to be launched. Even after it has been launched, it will likely take many months before an established trading range and market value for a carbon credit gets established.

Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to expect that the value of future traded carbon-credits will have at least some impact on the production, marketing, and selling behavior of automotive OEMs that will have to comply with the new policy and regulations. As suggested later in this blog, there might already be evidence that this is happening, with Baojun’s ramp up in sales, of the Baojun E200.

Profit margins and market demand (sales volume during recent months), are likely the most important variables that will determine future marketing and sales efforts for any given model. At the model level, profit margins are unknown, however sales volume data are available, and during the last quarter of 2018, 7,243 ei6 PHEV sedan were sold, while slightly fewer ei5 EV wagons (6,781) were sold. The sedan is priced somewhat higher than the wagon, and so for that reason alone we might expect profit margins to be higher. However, as illustrated in the first two rows of the table above, more than twice as many carbon credits are generated by producing the pure EV wagon, relative to the PHEV sedan.

Although I’ve used SAIC within this blog as a convenient means for exploring carbon-credits, ultimately, I’m interested in the bigger questions that will effect the industry and the environment – – such as:

-

- How will China’s expected 2019 NEV carbon-credit trading system impact OEM business decisions, about what types of cars to produce, in what quantities, with what profit margins?

- How valuable, influential – – or not – – will carbon-credits be – – in terms of their 2019-2020 (and beyond) impact on automotive OEM business decisions?

- More specifically, how will carbon credits impact corporate balance sheets and income statements, in terms of revenues generated, or if the credits get accumulated for a period of time (and not sold, or traded in the carbon market) does the value of those accumulated and held credits impact the value of the business or the corporate entity?

- To what extent will China’s policy push for NEV related carbon-credits – – in the long run, be a success or failure? After years or decades of implementation, how will the policies be viewed – – as significant or major contributors to cleaner air, less carbon in the atmosphere, a healthier China, a healthier world, and a changed automotive industry at national and global levels – – or not? Obviously, we’ll have to be patient, it will take years or decades – – before those questions begin to get answered.

In the short run, over the course of this year, we might more realistically point our efforts towards obtaining a better understanding of more concrete and near-term matters. For example, matters related to specific OEM businesses, or an industry sector, such as China’s automotive domestic OEMs. Unfortunately I’m not an accountant, nor do I have much experience analyzing balance sheets or income statements within this context of China’s changing automotive industry; so if there are a few accountants that might be reading this blog “out there”, or really any readers that might be able to shed light on these questions – – please don’t hesitate to use the comments section below, to shed new light on the questions raised above.

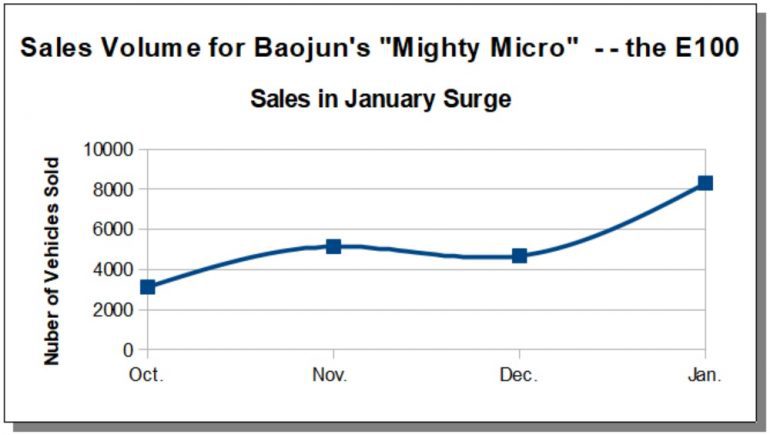

In the meantime I could not help but notice, that just a few days ago Jose Pontes, via his blog, EV blogspot, has shared new sales volume data for China’s January 2019, NEV best sellers. Thank you Jose! As acknowledged in the blog and comments, there are numerous challenges regarding data quality and data reliability, so users of this data are wise to take note. With that disclaimer, I do think it’s interesting that according to this source, January sales of the Baojun E100, are reported to be a whopping 8,312 units/cars. If confirmed, this would indeed make for a dramatic rise from the 4,692 units (up 77%) reportedly sold in December 2018. Sales volume for the last four months is shown in the graph below:

With the exception of a slight dip in December, Baojun’s micro, which perhaps should be renamed as the “mighty micro”, or something more fitting, appears to be selling well.

As mentioned earlier, Yang Jian, the managing editor of Automotive News China, noted more than a year ago, back in December of 2017, that Baojun has been given a new goal:

- Help GM expand into China’s EV market to meet Beijing’s production quotas. … (related to) a carbon credit trading program to goad automakers to ramp up output of EVs and help curb emissions and pollution.

That mission, seems to be right on track, as visualized in the graph above. More E100’s are not only being produced, but they also appear to be selling.

It will be interesting to see whether the Baojun E100 sales volume continues to rise, during the coming months.

From this blogger’s perspective, it will be even more interesting to witness the launching of China’s carbon-credit NEV trading system, and subsequently as this year progresses – – how the price of a credit evolves over time.

Even before that price gets established, there seems to be mounting evidence, that China’s policy is already beginning to have at least some of the impact – – that it was designed to have.

For a complete list of sources and references used in this article; click here.

Full disclosure: I do not own any shares in SAIC, or any other company mentioned in this blog.